Forum Recap: Comparative Human Rights

On Tuesday, 27 November 2018, the Research for Change Forum held its second Forum of the 2018-19 academic year: a Human Rights themed event, graced by three Bristol postgraduate students: Rodriguez Burr Matias, Abdulhakeem A Tijani, and Christopher Grey. Each speaker too some time to share about the focus of their research, as well as their methods.

Matias adopts a comparative law approach to discrimination; comparing and contrasting case law of the European Court of Human Rights, the US Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court of South Africa, with a goal to explain the underlying protected grounds of discrimination. If we organise a party and invite selected guests but not others, there can hardly be any legal discrimination found. To constitute as a grounds of discrimination, the claimant must possess a physical ground, status or characteristic - for example, their sex, race or disability. Discrimination is only wrong, morally and legally, when based on these characteristics, and Matias' research seeks to explore the ways these grounds are identified.

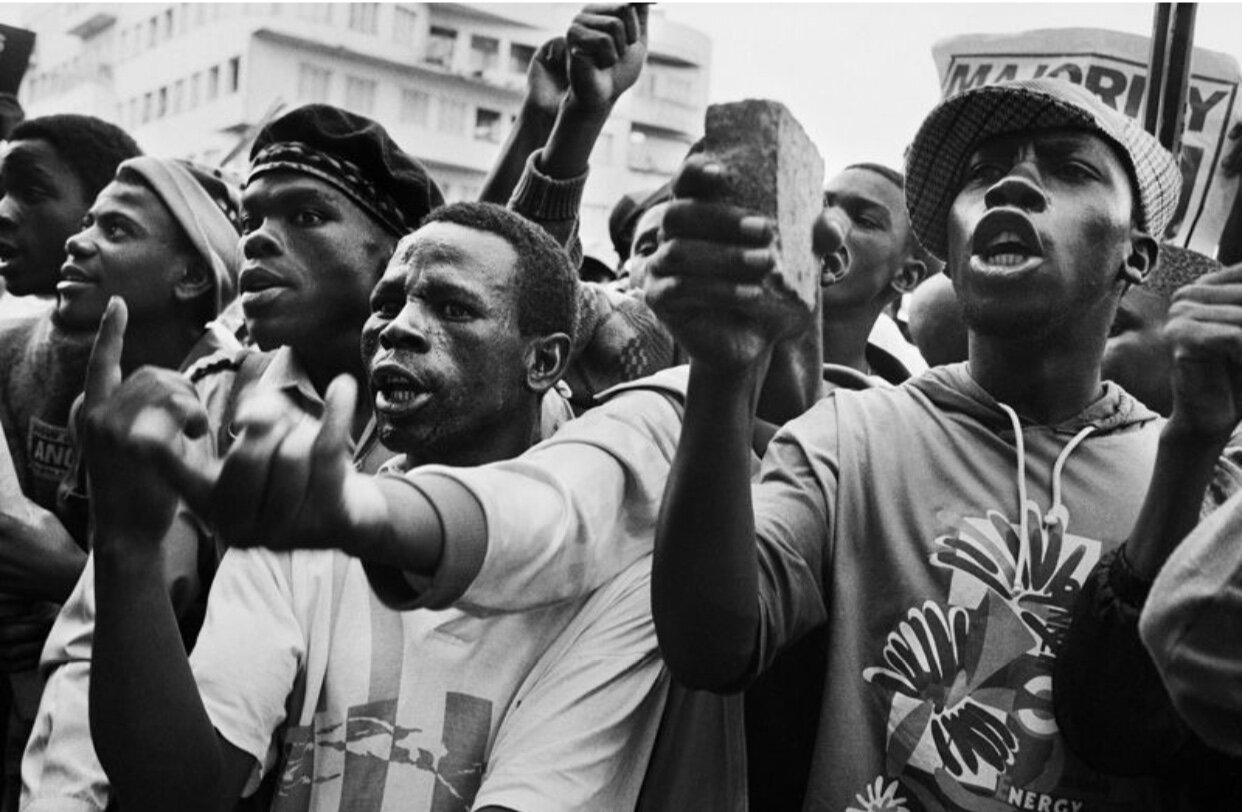

Factually, there are political and social movements behind certain grounds. For example, the suffrogate movement and civil rights movement dealt blows to gender and racial inequality, respectively. However, Matias seeks to delve further into the normative principles as to why such discrimination is wrong, via comparative analysis and comparative law. There is the problem of our own legal bias; we tend to examine other jurisdictions through our pre-conceived lens.

For one, the European Court of Human Rights has to use normative reasons to justify its inclusion as an unlisted grounds of discrimation - for example, that certain people who identify as a certain sexual orientation are vulnerable.

Matias' examines the European Court of Human Right's case law where new grounds of discrimination are recognised, for example, sexual orientation, illegitimacy of birth, health status, HIV positive status and trade union membership, just to name a few. These grounds were not originally envisioned or seen as just as important as other more 'conventional' grounds of discrimination. With case law of the Constitutional Court of South Africa and the US Supreme Court, he takes a specific approach, looking at groups associated with historical disadvantage, past and present political exclusion, and immutability.

Regardless of the common themes in Matias' comparative analysis, the courts employ different concepts; not all the principles can explain the definitive list of current unlisted grounds. So far, he has formulated three theories of non-discrimination and equality to examine the jurisprudential process of the judges in choosing new grounds of discrimination for recognition. 1) Discrimination as an individual right to equal treatment, 2) Discrimination as a means of redressing social inequalities, and 3) Discrimination and cultural domination. So far, judges appear to use all three methods to different degrees, leading to inconsistent results.

Abdulhakeem's work turns on the socio-economic rights of persons living with physical disabilities in Nigeria, seeking to examine how the legal framework in place extends rights and protection to the disabled, theoretically and in practice.

To Abdulhakeem, Nigeria seems to be one of the few countries in the world that sign almost any instrument of law into practice, but the extent of implementation is significantly more doubted. Nigeria has a certain track record of failing to implement its ratified international agreements on a national level, and in Abdulhakeem's specific study, the implementation of disability anti-discrimination practice. Two states even have actual laws on disability welfare, but have not implemented them to a large extent.

In his research, Abdulhakeem asks the following questions: Whether there is there a legal framework for socioeconomic rights, the factors that militiate against the integration of socioeconomic rights, whether there is any other legal basis for recognising and enforcing socioeconomic rights, and what the current judicial attitudes towards disability rights are.

He focus on traditional doctrinal legal research methods, complemented by empirical legal research methods, using a qualitative, not quantitative, model. Interviewing is his main instrument, with documentary sources and case studies with participant observation to supplement. The questions are unstructured, to allow for informality and flexibility. With a narrative data analysis method, he can also cover greater areas of interest.

Ultimately, Abdulhakeem aims to develop critical thinking and a comparative philosophical underpinning of his study, assessing how the concept of disability and discrimination is incorporated into the legal system. While some have entrenched it in their constitution, others have enacted discrimination legislation, and some rely on a mixture of both. He points out the ethical implications, including informed consent, confidentiality and data protection, and research integrity. His study is indeed important; there is very little literature available in Nigeria - literally, only one book, which in itself is a rough collection of articles. The study would serve as a new area of research under Nigerian Jurisprudence. If his study's reccomendations are adhered to, it would radically change the human rights regime in Nigeria.

Christopher's research assesses the right to a fair trial and the rules relating to the admission of self-incriminating evidence; in particular, focusing on the nature and character of the right to silence and its disparities in implementation across England and Wales, and The Gambia. So far, Christopher has used international law as a lens, supplemented with comparative and socio-legal processes.

Why The Gambia? Christopher explains that he was heavily involved with the University's Human Rights Implementation Centre and Human Rights Law Clinic. He also previously worked at the University of The Gambia's Faculty of Law. While he taught English Law, he gained the invaluable opportunity to work with Human Rights NGOs, for example, informing the police of human rights ideas. Christopher even spoke with a judge talking about the process of evidence; she said that if children confess, their confession carries legal weight, but was unsure what the actual law was. He also worked with the African Commission of Human Rights, based in The Gambia, and was able to interact with many in the sector.

While relatively early in his postgraduate research (3 months in), he wants his pHD to be an intersection of the various areas of law. That is not to say that he has not had his fair share of difficulties so far; he has had to revise his research questions after two months, as his ideas would not play out optimally in literature.

One aspect of his research is historical; how did criminal justice systems emerge and develop in British Colonial Africa? Another is comparative, though at this stage he is unsure whether comparative analysis can be done cohesively, with current scarceness of research. The Gambia is a country of less than 2 million people, and African countries have generally very little research funding.

Christopher currently uses interviews, ethnography and archival research. He has three main approaches: epistemology - how can one claim to know, or generate knowledge about something? The second is positionality - how can a researcher shed cultural and legal bias and avoid superimposing those concepts into a foreign legal system? The last is power and ethics - where does power lie in his research, who gains from it, and who's voice is presented?

The Research for Legal Change Forum most sincerely thanks Matias, Abdulhakeem and Christopher for their valuable time and expertise, and wish them all the best in their research. On a more personal note, I found this session to be one of the most captivating and engaging, though a Forum Recap doesn't do it justice. Connect with us to be informed and updated of future events and Forums like this!